August 2017

“Corporate suicide.” That’s how two researchers, Robert Ayres and Michael Olenick, are now describing the stock buyback boom in the U.S. economy.

For the uninitiated, buybacks are the process by which a corporation buys up its own shares using company cash. Typically, this will result in the short-term increase of a company’s stock price—and will often trigger certain bonus payouts for corporate executives. Since 2010, over $3 trillion has been spent on buybacks by American companies. (Translation: Buybacks are a huge deal.)

It’s been my long-standing contention that buybacks are bad for the U.S. economy, and extremely dangerous for unsophisticated and long-term investors. Why? Buybacks may inflate short-term earnings for the benefit of corporate executives and savvy activist hedge funds, but they harm long-term shareholders—like pension funds and retirees—because they allow managers to siphon away corporate cash that could have otherwise been spent on innovation, employment, wages, or expansion that would ensure the future success of the business.

As the economist William Lazonick put it in our conversation with him in June, it’s all about “value extraction.” Lazonick’s research has shown that from 2003 to 2012, companies in the S&P spent 54% of their earnings—a total of $2.4 trillion—to buy back their own stock.

Much of that cash, in my view, has been wasted. For instance, consider HP, a company that has spent $82 billion on buybacks over the last two decades. Today, the company is worth a fraction of that. Just imagine if even a small percentage of that capital had been redeployed to growth initiatives or other innovation programs. Of course, it’s not just HP that offends: I have written previously about dangerous buyback programs at companies like Cisco, American Airlines, GM, and many others—all of whom seem to prefer buybacks over innovation. (As a rule, Nightview Capital does not invest in companies that do buybacks.)

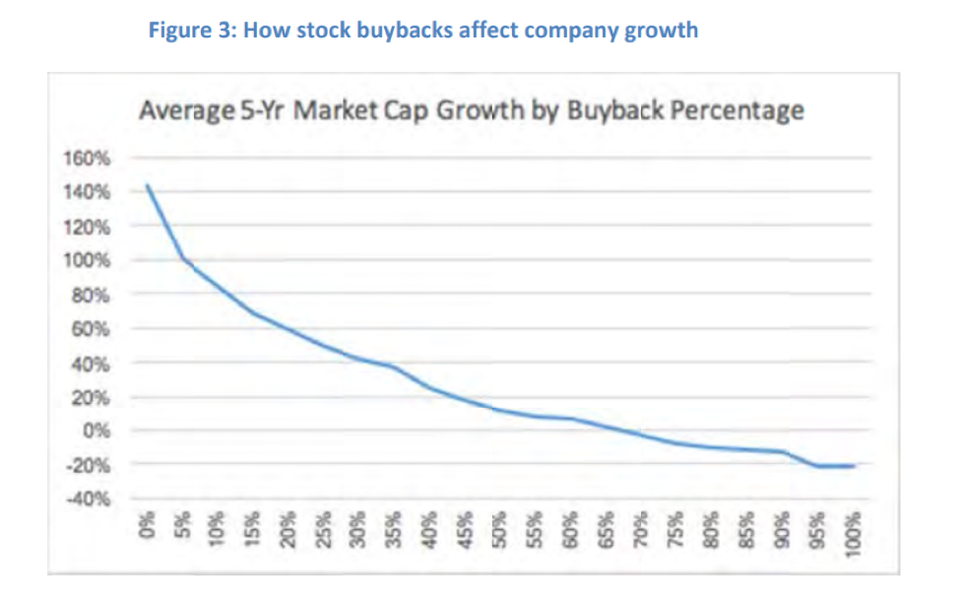

Now, back to the research. In July, Robert Ayres, the Emeritus Professor of Economics, Political Science and Technology Management at INSEAD, the French graduate business school, along with his colleague Michael Olenick, an executive fellow at INSEAD, set out to explore the correlation between buybacks and the market value of businesses that do them. You can read their paper in full here (.pdf), but I’ll save you the suspense: Not only do buybacks not lead to growth in a company’s market value, they are strongly correlated to a declining market value of the company. The chart below makes it crystal clear: A company’s market cap goes down as the amount of buybacks goes up. (This chart is published—with permission—in their report.)

Put another way: the more a company spends on buybacks, the less likely that company will see long-term growth in market value. “We find that excessive buybacks in the past decades are a significant cause of secular stagnation, inasmuch as they effectively reduce corporate R&D while contributing, instead, to an asset bubble that creates no value,” the two researchers conclude in the summary of their report.

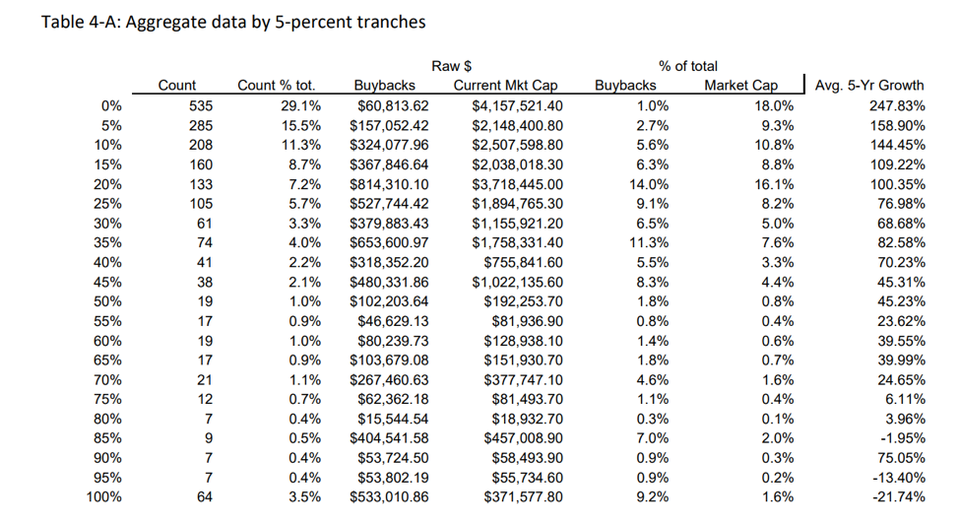

Specifically, their research investigated buybacks at 1,839 U.S. firms worth more than $100 million, and a total of of 6,516 buyback transactions. Now take a look at the chart below.

According to Olenick and Ayres’ research, the top tranche of 535 firms that repurchased less than five percent of their market value saw their market value increase an average of 247.8 percent over the prior five years. On the other hand, the bottom tranche—or the 64 firms that repurchased 100% or more of their market capitalization—experienced a 21.7% decline in value over the same timeframe,” according to their research.

Shortly after the publication of their report, we reached out to speak with Ayres and Olenick about their research. An edited transcript of our conversation is below, but Michael Olenick summed it up quite nicely. The data, he says, are clear. “When you buy back too much of your stock, you’re going to cause your company to fail to grow,” he says.

Nightview Capital: What made you interested in the subject of buybacks to start with?

Michael Olenick: So my back story is I actually work for a totally different group, and this started out as a skunkworks project. Bob asked me if I can help with some data analysis. I did a lot of work during the financial crisis, and as we began to pour through these numbers I was really surprised. These numbers just really popped out enough to where to where my [superiors] said OK fine spend some time and check into this.

What we found, and what seems really clear, was this correlation that the higher the buybacks as a percentage of your company’s value, the slower your growth. And it was so obvious to the point where, you know, we put together the numbers, double checked them, updated them and said, “Okay, are we missing anything?” We pulled in revenue, we pulled in different measures and just nothing we did seemed to really change it.

For the most part, when you buy back too much of your stock you’re going to cause your company to fail to grow—and that sort of makes sense.

Robert Ayres: My serious interest in getting into this first place has to with economic growth. Above all, I think that these buybacks are much bigger than most people believe. A large number of companies are spending more on buybacks than they earn, and their entire earnings (plus borrowing) is going into buybacks.

What that tells me is that the corporate R&D was once a major driver of economic growth. And cutting R&D can lead to a slowdown in growth. This is really important to understand.

If you go back and look at the history of a company like Nestle: it started out in baby food, and their first product was condensed milk. But there’s clearly no longer a market for condensed milk, but luckily they came up with other things, like chocolate milk and instant coffee—which is their cash cow. Without innovation and R&D, you have to ask: What about the coming future? That’s what’ll get chopped.

Olenick: Right. It’s the growth initiatives that are vital. They’re expensive and risky—they call them an investment for a reason—but they should have strong returns. But if you chop off your growth initiatives and then you just start borrowing money to jack up your stock price [by buying back stock]—it’s going to cause long term problems. And we see that when you look at the top of our list.

NC: We have our own thoughts about why so many companies do buybacks. What are your thoughts? In other words, what has caused the buyback mania that we’ve seen over the last two decades?

Olenick: Short term greed and executive compensation.

Ayres: Both of the above. It goes back to the principal-agent theory in economics that was introduced in 1976 at Harvard Business School. The idea that companies that are run by their owners have a much longer time horizon. But when the when the manager is an agent—he’s just hired hand he has only a very short expected life in the company—that’s the case now with most of these guys. They only look to their own benefit because they don’t have true long term interest in the future of the company. It is that simple.

And then, so many corporate compensation packages have been tied to stock price because nobody can think of any better metric. So it comes back to the idea that the stock price is the only available short term measure for compensation. And the problem is that it’s bad one. Because if they only look at the stock price [to determine compensation], they’re going to kill their corporations in the long-run.

NC: You have that sentence in the report that stands out to me, and it refers to buybacks at “corporate suicide.” Are there any specific companies that come to mind in terms of the “worst offenders” in this sort of realm?

Olenick: All of the ones above 100% [of earnings]. I’m looking at the list right now: Sears, I have no idea what they were thinking. HP has bought back about$81.5 billion of their stock. Seriously? Barnes and Nobles—they’re almost out of business. Abercrombie and the Gap—the same thing. Look, the list just goes on and on. Look at these numbers: the Gap spent $17.3 billion buybacks; if they had spent that money on growth initiatives, especially online ones, they probably wouldn’t be struggling like they are right now. They’re closing their stores and firing their employees, and I’m not quite sure how the money went into buybacks. Lots of these are retailers are over-spending on buybacks.

NC: One thing we see a lot is companies talking about “returning capital” to shareholders through buybacks. Given your research, is that accurate?

Olenick: The way companies return money to shareholders is dividends. That’s straightforward. If you want to return money to shareholders, just do a dividend. Buying back stock is this round-a-bout, screwy way that may work or may not work. And it certainly doesn’t lead to growth.

Ayres: The implication of this language (i.e. “returning capital”) implies that these shareholders are providing the capital in the first place. Which, in 99.9%of the time, they didn’t. It was people who came in much later. So when Nelson Peltz organizes a campaign, as in the case of Heinz, who are the shareholders they’re returning capital to? It’s the owners of 3G capital. It’s Brazil’s richest man. They did not invest in Heinz at any time. This is why I’m focusing on the activists: they do not invest their own money in any of the businesses that they attack. They are only there to make short-term gains and then take their money away.

NC: What about the risks for shareholders? It’s something that we’ve talked about internally, but how do you communicate the risk buybacks impose on shareholder?

Robert Ayres: You tell them that the company’s growth will slow up, depending on how much the buyback is. The more you have spent on buybacks, the lower the prospects for future growth are. You know, as we said, the more money spent on buybacks, the lower the prospects for future growth are—and yes I think shareholders should be aware of that.

NC: What do you think of managers that choose buybacks above other initiatives?

Olenick: I worked a lot in the industry before. I’m not really an academic, I’m kind of new to all of this. And I just know from my time in businesses that there’s just different manager mindsets and certain cultures in the way businesses operate. And if you have senior management of a company who is comfortable buying back enormous amount of their stock, they’re very likely taking it out of growth initiatives, or not taking their work initiatives very seriously… this goes into how a company is managed overall.

So if you have a manager who doesn’t know what to do with capital, and the best thing that they could come up with is to buy back their own stock—they’re either dishonest or incompetent. And it’s going to lead to not just issues with the stock, but it’s going to lead to other parts of the business as well: they’re not going to hire the best managers and it’s not going to be a good place to work. You’re not going to attract the best employees, and buybacks just…cascades through everything else.

Disclosures:

Nightview Capital, LLC does not accept responsibility or liability arising from the use of this document. No document or warranty, express or implied, is being given or made that the information presented herein is accurate, current or complete, and such information is always subject to change without notice. Shareholders and other potential investors should conduct their own independent investigation of the relevant issues and companies involved in this article. This document may not be copied, reproduced or distributed without prior consent of Nightview Capital.

Nightview Capital, LLC is an independent investment adviser registered in the Investment Advisers Act of 1940, as amended. Registration does no imply a certain level of skill or training. More information about Nightview Capital including our investment strategies, fees, and objectives can be found in our ADV Part 2, which is available upon request. WRC-17-20